An In Depth, 2002 Technical Analysis Of The Seiko "Black Monster" SKX779 From 2002

A pioneering early example of the Internet technical watch review.

Nearly a quarter century ago, a young watchmaker showed that a watch need not be expensive to be taken seriously. Then as now, there were many who could not afford to experience the joys of owning a Patek, Vacheron, or Audemars Piguet watch, but the independent watchmaking world had already welcomed F.P. Journe, De Bethune, and founding members of the AHCI, and of course in 1994, A. Lange & Söhne had introduced their first four models. It was also the beginning of appreciation for the appeal of less expensive and more accessible watches, and the realization that while less costly, they could be just as rewarding in their own right.

I was in grad school at the time and was an habitué of ThePuristS.com, where we affected to be above the rough and tumble of Timezone.com (this despite the fact that many collectors and enthusiasts went happily back and forth between the two) and in 2002, John Davis, who has gone on to enjoy considerable professional success for arguably the single most important watch brand in the world, took it upon himself to review an arguably entry level watch: The Seiko “Black Monster” SKX779.

The genre of the online technical watch review had been more or less single-handedly established by Walt Odets, and his was the standard which John (and I, in later writing) would attempt to match. It was John’s thesis that an intellectually rigorous examination of this early example of an enthusiast driven success story, would welcome folks to the watch enthusiast world who might be apprehensive of entering, and would also show established collectors that there is more to value than a price tag. And, it would also demonstrate that, as the article says, that first and foremost, watches are machines. I present to you therefore, the 2002 review by John Davis. (All article photos by John Davis, 2002).

The Seiko Diver’s 200 Meter SKX779, Featuring The 7s26 Movement

Watches are machines. While some of them may also be works of art, they cannot escape their machineness. There is undoubtedly something fascinating about those examples of the watchmaker's craft, but there is also something to be learned from the droves of micro-machines that are designed and constructed with only performance and economy in mind. There is craft involved in the ability to engineer a movement for production runs in the tens of thousands that is wholly other than the craft involved in manufacturing a movement by hand. It is a skill that I respect and admire, while having even less understanding of its intricacies than I do of traditional watchmaking skills. Being a fan of Seiko's watches though, I won't let my ignorance get in the way of taking apart the 7S26 in an attempt to discover its hows and guess at its whys.

The 7S26 automatic movement is a logical step in Seiko's entry level mechanical movement line. Replacing the 7002 in their popular Diver's watches, it incorporates quickset day and date displays (the 7002 was date only), automatic bi-directional winding via Seiko's patented Magic Lever system, and the lack of manual winding capability that has become a signature of sorts in entry level automatics from Asia. The watch I will be dismantling for this exercise is the SKX779, a 200 Meter Diver's watch sold (exclusively?) in New Zealand and Australia.

The Case, Dial, And Hands

The SKX779 is a large watch. Its case is 41.5 millimeters across without the crown and approximately 12.5 millimeters thick including the domed crystal. It has a very pronounced, scalloped bezel with circular graining that is protected by an equally pronounced bezel-guard that extends upwards from the lugs. While there are those that rightly question the functionality of this design (arguing that sand and dirt get into the space between them and cause the bezel to jam), it is undeniably this curious feature that attracted me to this watch. The bezel guard extends into the crown guard thanks to the location of the crown at the 4 o'clock position. This crown position is more comfortable for such a large watch and is a bit of a trademark with Seiko Diver's through the decades.

The dial of the SKX779 has an upward curving minutes chapter that gives it a wonderful depth. This effect is further enhanced by the domed crystal, which lamentably protrudes just slightly beyond the bezel (making it susceptible to scratches). A domed crystal is advantageous on a diver's watch as flat crystals can sometimes have a mirror effect under water.

Each of the three hands has a slightly different interpretation of a rocket-ship shape and when the hour and minute hand line up, the resemblance is pronounced. They are painted with an ecru color that matches the hour markers and both are filled with Lumibrite (Seiko's proprietary version of Super-Luminova) and, especially when brand new, glow as brightly as any watch I've seen. I'm always disappointed when watch companies use white day and date rings on a black dial and this is one of the few complaints I have about the classic Seiko Diver’s. The color scheme of this watch's dial gets big points from me for the use of black rings with white letters/numbers. Taken altogether, the shape of the hands and case and the depth of the dial through the domed crystal have a vaguely ray-gun gothic effect that I find very appealing.

The strongest feature of this version of the Seiko Diver is the bracelet and clasp. The solid link, brushed steel bracelet with polished accents is incredibly sturdy and well designed. It is heavy enough to balance the hefty case well on the wrist and has a wonderfully secure, two-button folding clasp with safety and a wet-suit extension. In addition to providing the peace-of-mind that this bracelet and clasp will in all likelihood never come off of your wrist accidentally (either by breaking or coming unhooked), it has the flexibility to be extended sufficiently to wear over a wetsuit at a moments notice. The links are held together by solid pins with sleeves that are a little tricky to remove and replace but not unduly so. Attaching this wonderful bracelet to the case are the two largest spring bars I've ever seen.

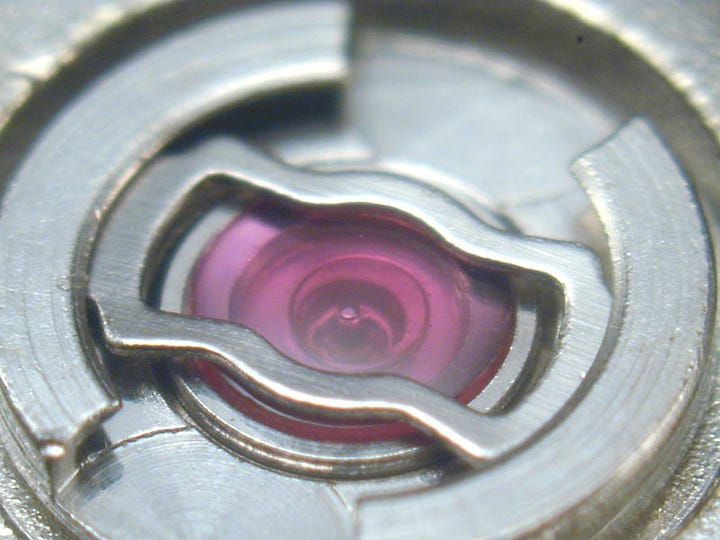

Above, upper left, 7S26, upper right, spacer ring, bottom left, rotor, bottom right, Diashock antishock spring.

In addition to water-tightness, the ability to withstand abuse is a highly desirable feature for a utility watch of this nature. The Seiko Diver has several features that contribute significantly in this regard and a few of them are visible upon removing the solid steel back. The 7S26 uses Seiko's patented Diashock shock protection on the balance pivots, has a soft, plastic spacer ring closely integrated with the movement and a relatively low mass rotor that is unlikely to bend or break even with very severe shocks. The plastic spacer ring, combined with the sheer massiveness of the case, provides a great deal of additional shock resistance and is a more economical solution than a metal spacer ring as well. This combination of economic and sensible engineering is a trend that persists in almost every facet of the design of the 7S26 movement.

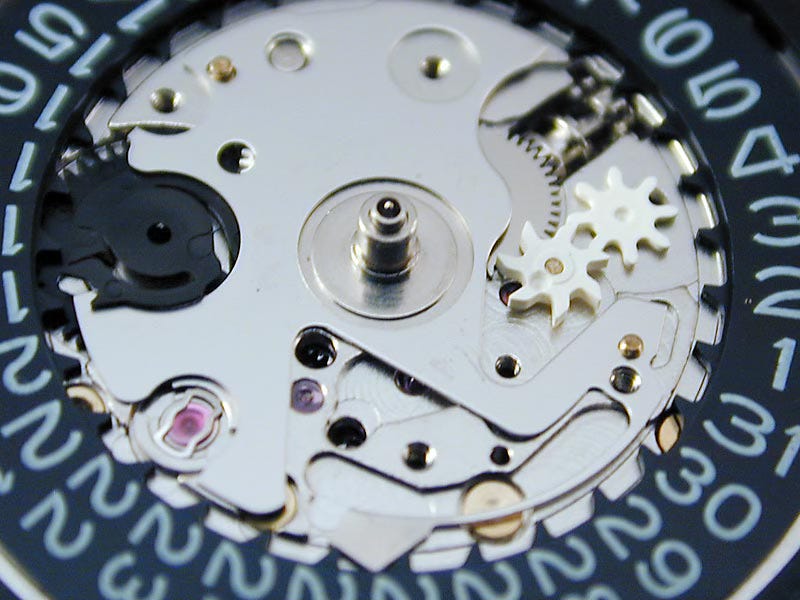

Under The Dial

While there is often much disdain amongst watch enthusiasts for plastic components in mechanical wristwatches, I propose that there are instances where it is acceptable and possibly even preferable. One particular area in which plastic is a perfectly logical solution is the calendar mechanism. These are parts that rotate at very slow speeds (or sometimes intermittently) and with very little torque for the majority of their rotation. This combination of features makes them controversial with regards to lubrication. While lubricating them significantly will increase the drag on the movement and possibly ultimately stop the watch, leaving them sparsely lubricated or dry will ultimately result in wear. Plastic is an ideal solution for these components because it is light and self-lubricating. I won't pretend that Seiko's primary concern here is not one of economics, but it is combined with intelligent engineering as well.

The plastic parts in question are the quickset wheels, the intermediate calendar wheel and the calendar advance wheel. The calendar advance wheel has two plastic fingers to advance the date and day disks, that will easily slip out of the way if the quickset is activated while the calendar is advancing. The calendar mechanism is secured under a very thin but nicely polished metal plate that is held in place with three standard screws and one Phillips head. The presence of this one tiny Phillips screw in the movement is something of a mystery and along with the molded plastic and thin metal plates lends the bottom plate the appearance of a very well made calculator.

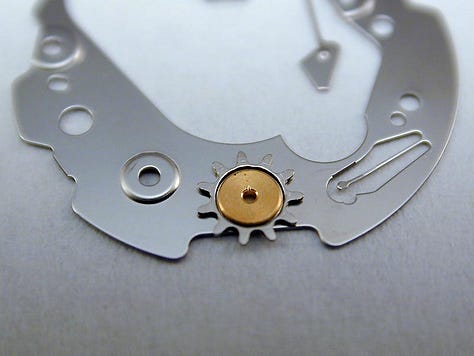

Above, top row, L-R: calendar advance wheel, first wheel in quickset mechanism, clutch and quickset pinion; bottom row, dial, and under dial works with day of the week ring removed

After removing the calendar plate we can also observe the oddly shaped teeth of the clutch and quickset pinion, all the more visible because of the utter lack of keyless works on the bottom plate. Because there is no winding pinion (no manual winding capability), in its place is a quickset pinion. The square teeth of this pinion mesh with identical teeth on the clutch when the stem is in the second position and allow the quickset pinion to turn in either direction: clockwise to advance the date and counterclockwise to advance the day indicator. The second quickset intermediate wheel (the white plastic wheel with traditional teeth) then slides into engagement with either the date ring or the third intermediate wheel (with the wolf teeth) which advances the day disk. This is a very functional and robust quickset and calendar mechanism and, being largely made of plastic components, requires no lubrication. Another thin plate holds the intermediate calendar wheel, calendar advance wheel and hour wheel in place and after removing them we can contemplate the top plate of the movement.

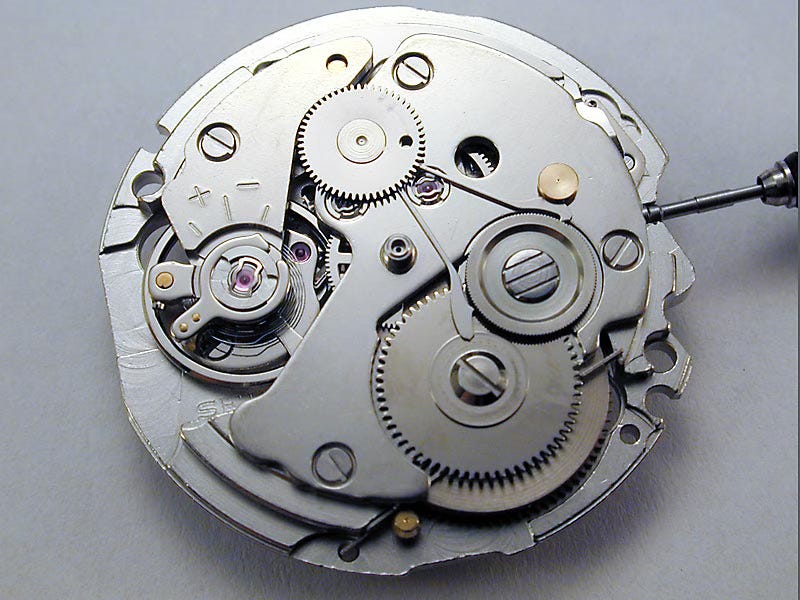

The Automatic Winding System

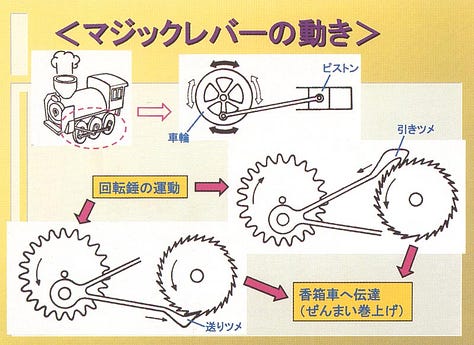

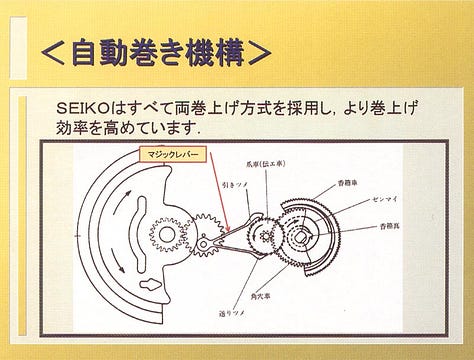

One of my favorite features of Seiko automatics is the Magic Lever winding system. Earlier versions of this winding system involved only three moving parts: the rotor, the Magic Lever and the pawl wheel.

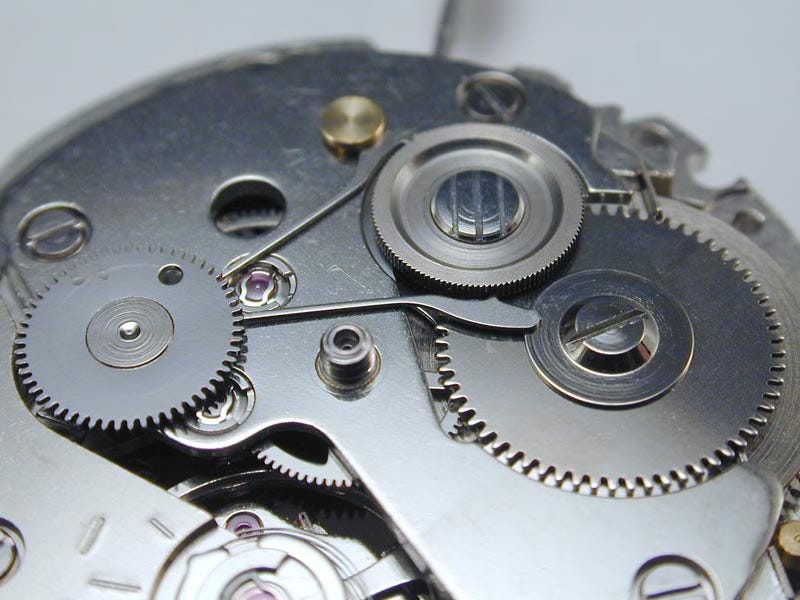

Current implementations use one extra wheel for a total of four moving parts. This simplicity of design adds to its robustness while maintaining a high level of functionality. Along with the lack of manual winding, it makes the 7S26 one of the simplest automatics around. The basic functioning of the Magic Lever system can be understood from these diagrams from a Seiko Credor catalog. The coupling between the lever and the intermediate wheel functions on the same principle as a locomotive (or a choo-choo as shown in the diagram). The two arms of the Magic Lever then drive the pawl wheel. They alternately pull and push the pawl wheel in the counterclockwise direction as the intermediate wheel rotates in conjunction with the rotor. The intermediate wheel and pawl lever cannot be removed until the ¾ bridge is removed as the intermediate wheel is held onto the bridge with a semi-circular clip on the underside of the bridge.

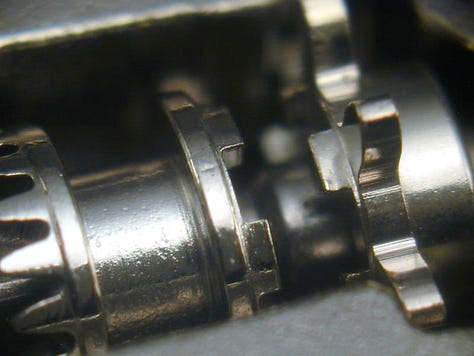

Above, L-R, Magic Lever diagrams, magic lever; bottom L-R, wear under pawl wheel, retaining clip for intermediate winding wheel

For the sake of comparison, an ETA 2892 winds the mainspring arbor one rotation with 155 turns of the rotor. The current implementation of the Magic Lever winds the mainspring arbor one rotation for 166 turns of the rotor. Another factor to consider when contemplating automatic system efficiency is the dead angle. The dead angle is the angle of back and forth movements that the rotor can experience without any winding energy being transmitted to the barrel. The dead angle of the Magic Lever is slightly larger than in the 2892 (by five degrees or so) although I haven't precisely calculated either. There are many other subtle factors that effect the efficiency of an automatic system but I feel safe in assuming that Seiko's system is slightly less efficient than ETA's (at least the 2892, which differs from the 2824 and 7750). ETA's automatic systems are remarkably more complex and expensive to manufacture though and I've yet to hear of a Seiko automatic that does not wind sufficiently in use. It is not at all uncommon to find some wear around the lever arms and intermediate wheel coupling in older versions of the Magic Lever system. This example showed some wear underneath the pawl wheel. This amount of wear is fairly significant for a watch that is less than two years old. On the whole, the automatic system is a triumph of simplicity that comes with some apparent sacrifices to longevity as well as efficiency.

Thanks for this terrific callback to the early days of ThePurists.com, Jack--I still miss those wonderful articles, not to mention the often endless and hugely civil conversations on the various sub-forums. And for me, that word--"civil"--was vital; far from being an affectation, for me the incredibly welcoming, friendly, and helpful tone of that site and the threads it encouraged were unparalleled. I was a total newbie to ANY online forum when I first dared to submit a post to ThePurists.com, and from then on, from Dr. Mao to the various moderators (very much including a certain Jack Forster!) to the many thoughtful and friendly posters (including one incredibly knowledgeable ei8htohms) I ended up finding a home there. Comment sections can be good, but oh how I miss a great forum!

This is the opposite of a Malaika article