Notes From Japan: Iida City And The Citizen Watch Co.

A remote mountain valley is the home to one of Citizen's most historic factories.

I’m writing this on September 16th, in a hotel room in Roppongi Hills, Tokyo, which is an extremely upscale district with a full complement of luxury hotels, stores, and and restaurants (Sukiyabashi Jiro Roppongi, a sushi restaurant helmed by Chef Takashi, the younger son of sushi legend Jiro Ono, is in Roppongi, just to give you an idea).

Several days ago, though, I was with the Citizen Watch Company in a very different location: Iida City, in Nagano Prefecture, which is more or less 150 kilometers from Tokyo as the crow flies, but closer to 260 kilometers as the car drives. This is thanks to the presence of the Japanese Alps in between the two cities – a range of extremely rugged mountains which more or less bisect the main island of Honshu and which form a formidable natural barrier. The Japanese Alps are difficult to cross under any circumstances, but especially in winter when heavy snow can make many of the high passes impossible to traverse – so much so that the crossing of the Hida range by a military expedition led by the daimyō Sassa Narimasa in 1584 is remembered as a major historical event.

Citizen has a number of different manufacturing centers throughout Japan, including one in Tanashi, Tokyo, and the Miyota factory in Nagano Prefecture (where Iida City is also located) but the Iida factory is historically important, having been founded in 1945 in order to move manufacturing away from Tokyo to an area unlikely to be subjected to bombing. In an article on the history of Citizen for Watchtime, Joe Thompson wrote:

“During the war, Japanese watch firms shifted production from dangerous Tokyo (Citizen and Seiko factories were damaged by Allied bombs) to the relative security of the Japanese Alps. Citizen opened a facility at Iida in Nagano prefecture in the Alps. The original Iida factory is still in operation today and has been declared a historical building by the city fathers. (Citizen has mixed feelings about the honor: it would love to update the building but cannot because of the historical building designation.)”

The factory today still has a strong aura of history and the surrounding landscape only emphasizes the sense of standing somewhat apart from the modern world – which is not to say that the Iida facility does not do state-of-the-art watchmaking. Entry into the manufacturing area is NASA clean-room level, requiring you to don coveralls and hairnets (may the unflattering picture someone took of me looking like a disgruntled food service employee never find its way to the Internet) and pass through an airlock with an air shower that blasts dust off you. Inside, one of the areas is home to what Citizen calls its Super Meisters – its most elite watchmakers, each with over 30 years of watchmaking to their credit, who assemble Citizen’s most high end watches, including the ultra thin Eco-Drive 1 (the world’s thinnest light powered watch, at 1mm for the movement and only 3mm overall, an amazing engineering achievement which represents decades of refinement of Eco-Drive technology) as well as the Caliber 0100, which is the most precise watch ever made, with a maximum deviation in rate of just one second per year (and that is the maximum deviation; in practice I suspect any drift would be unnoticeable to the owner).

“Japanese Alps” (Nihon Arapusu) isn’t a nickname, as I’d first thought – it is the official collective name of the Hida, Kiso, and Akaishi ranges although the name was actually coined by an English archaeologist named William Gowland, and made more broadly popular by the Anglican missionary Walter Weston, an enthusiastic mountaineer who published Mountaineering and Exploration in the Japanese Alps in 1896.

The mountains make getting from Tokyo to Iida something of an expedition – you cannot follow a straight road between the two cities, as there isn’t one. Instead, you have to drive more or less east from Tokyo and then north to Suwa City, where you can turn south again and travel through a narrow valley until you get to Iida. The Alps are so rugged that building a road going directly through them is impractical, so the Japanese government began a very ambitious project to connect Tokyo and Nagoya with a train tunnel. The train will be a Shinkansen high speed train levitated above the track bed by magnets (maglev) and will be very deep – nearly 5,000 feet below the surface at one point. As of 2019 I’ve read that the project is stalled by concerns from Shizuoka Prefecture about environmental impacts but if completed the train would be able to make the Tokyo-Nagoya run in 40 minutes. Whether this will cut travel time to Iida, I don’t know, as the tunnel is too deep in many places for there to be a station on the surface.

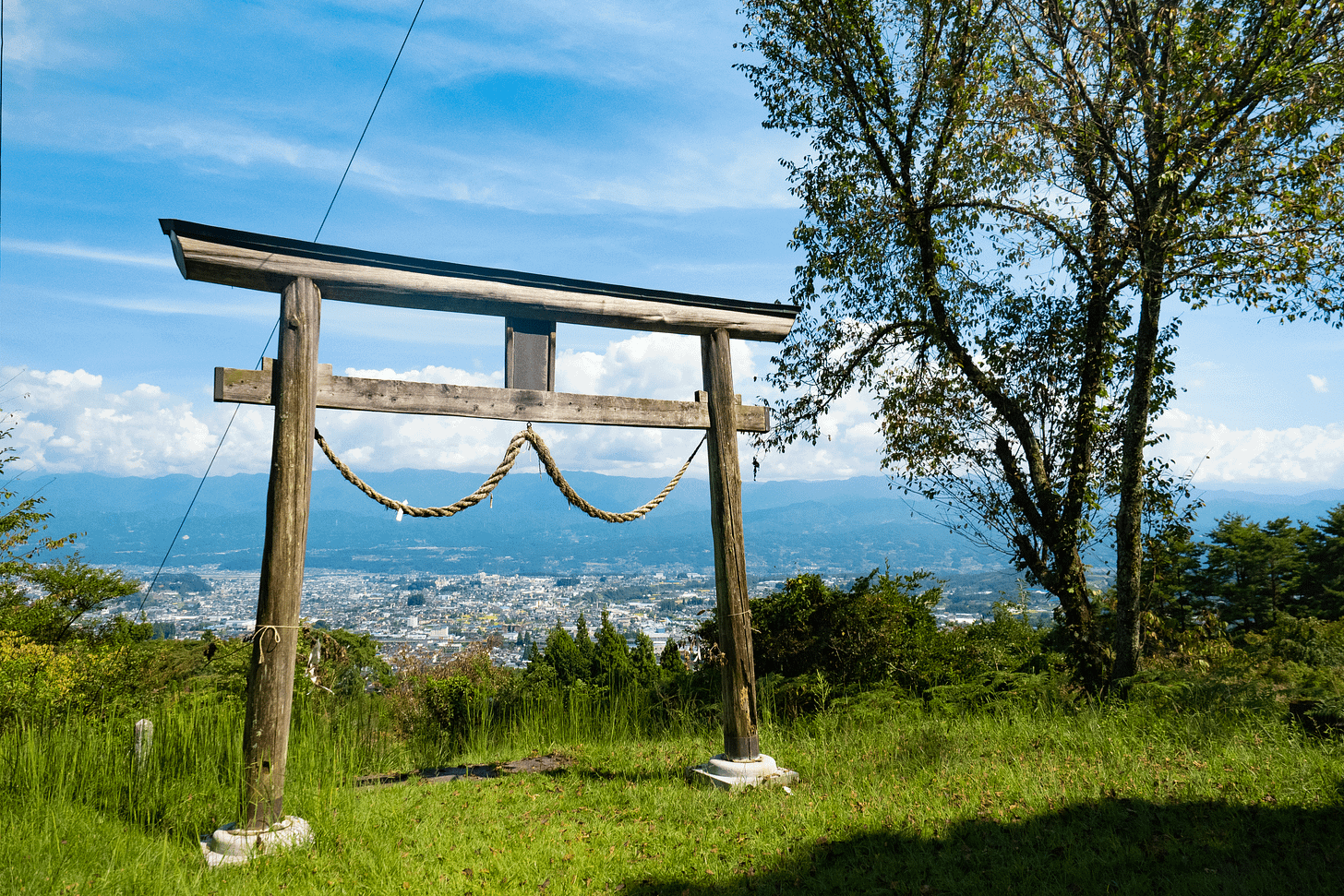

Thus, much of the Japanese Alps may remain remote and difficult to reach even if the tunnel is finished on time (in 2027). There is a tradition in many parts of the world of retreating to the mountains to practice meditation and other ascetic practices and in the Japanese Alps, practitioners of Buddhism, Shinto, and the religion known as Shugendō have often traveled. Shugendō, I have read, is a combination of Shinto and Buddhist ascetic practices and recognizes a large pantheon, including deities from Tibetan Buddhism.

In 1907, a Japanese expedition summited Mount Tsurugi, then thought to be the last unexplored mountain peak in Japan. At the summit, the expedition found metal ornaments from a metal cane and sword mountings – the peak had been visited by a shugenja a thousand years before.

Watchmaking has its own kind of asceticism – one of unbroken concentration and unflagging attention to detail – which is perhaps why it’s often practiced in remote mountain regions, like the Swiss Jura, where there are, presumably, fewer distractions.