What We Got Wrong – And Right – About The Breguet Magnetic Escapement

A watchmaker from Breguet clarifies some of the finer points.

Hello gentles all – this post is free to all readers; a quick update on the Breguet magnetic escapement. I know, I know, just when you thought we were done 😃.

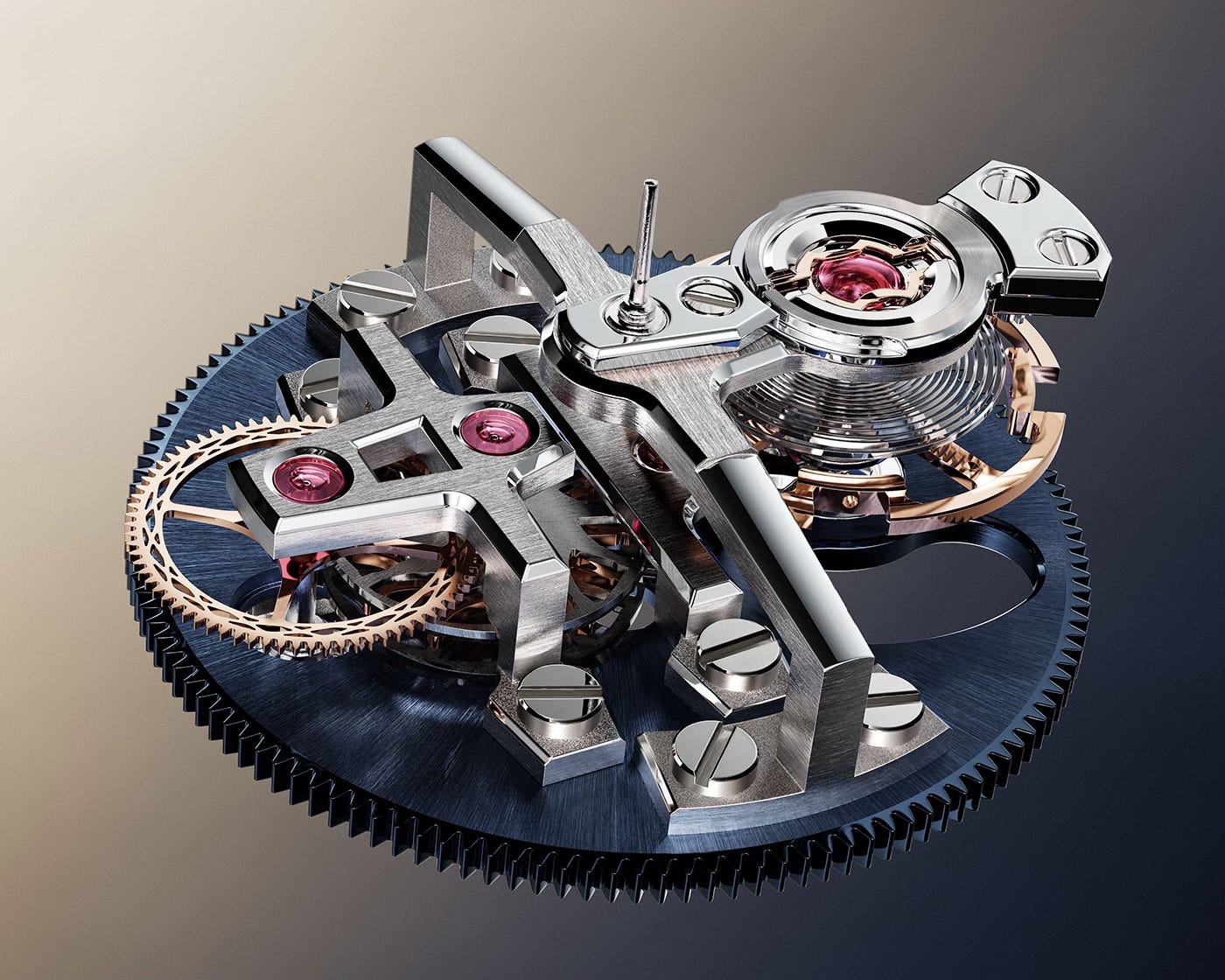

Covering the Breguet magnetic escapement has consumed quite a lot of the collective time, energy, and effort of the watch community since it was announced on December 1st. The escapement has proven challenging to cover, since it relies on magnetic fields to impulse the balance, unlike all other mechanical escapements, which rely on physical contact between escapement components. While much of the technical coverage (including my own for The 1916 Company) got a lot of the basics right, there were still some points that remained unclear from the materials available from Breguet.

The point most widely discussed, is whether or not the pallets of the escapement lever make direct physical contact with the safety wheel, which is sandwiched between the two magnetic wheels of the escapement. A quick review:

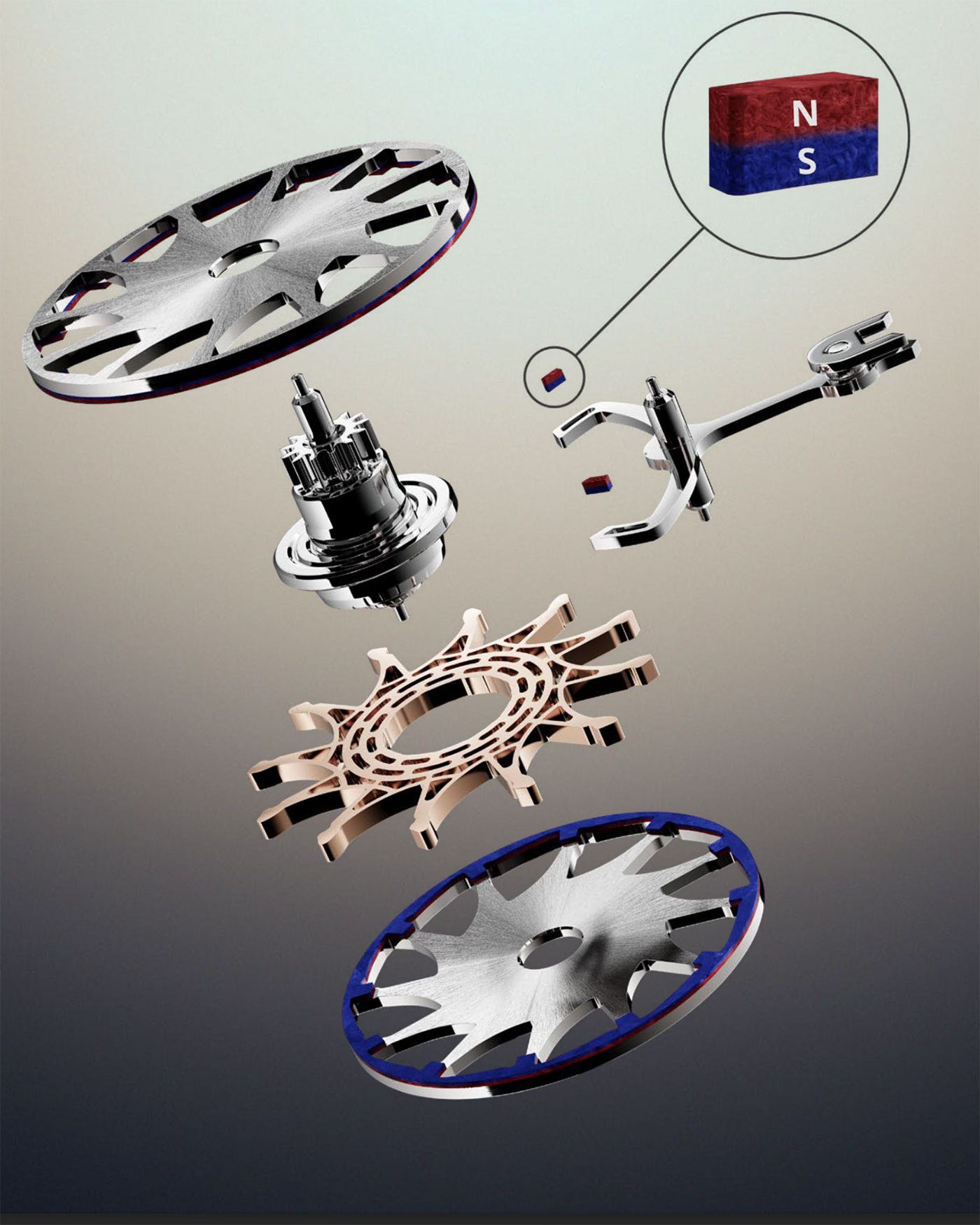

The escapement consists of an escape wheel in three layers, with a lever with two pallets which interact with the escape wheel; at the other end of the lever is the fork. The balance unlocks the fork at the beginning of each cycle of the escapement as the impulse jewel passes through the fork, lifting one of the pallets clear of the escape wheels and causing the other pallet to drop into the gap between the escape wheel “teeth.” The pallet which is lifted clear of the escape wheel teeth is propelled away from them by the repulsion between like magnetic fields, generated by the upper and lower surfaces of permanent magnets embedded in the pallets, and the magnetic rings on the inner faces of the outer two escape wheels.

This is the arrangement of the magnets, showing their polarity:

As the impulse pallet is pushed away from the escape wheels, the stack begins to rotate. A key point is that the escape wheel does not rotate until well after the pallet has cleared the escape wheel stack and the stop wheel tooth.

The opposite pallet then drops, and the escapement is ready for another cycle.

I had the opportunity today to talk to a watchmaker from Breguet who was able to provide some clarification on a few points which may be of interest.

The first, is that the “stop wheel” actually does make physical contact with the pallet at each drop. (This was a major clarification as it was not clear whether the stop wheel was only present as a safety feature to prevent the escapement from skipping in case of a shock, or if it was actually active on every cycle of the escapement.) However, the pallet then recoils slightly (although the clearance is minute) and is not in physical contact with the stop wheel when it is unlocked. This is essential to ensure there is no sliding friction during impulse, and is essential also in ensuring that the impulse energy is independent of the energy of the going train – which is to say, essential to making this a true constant force escapement.

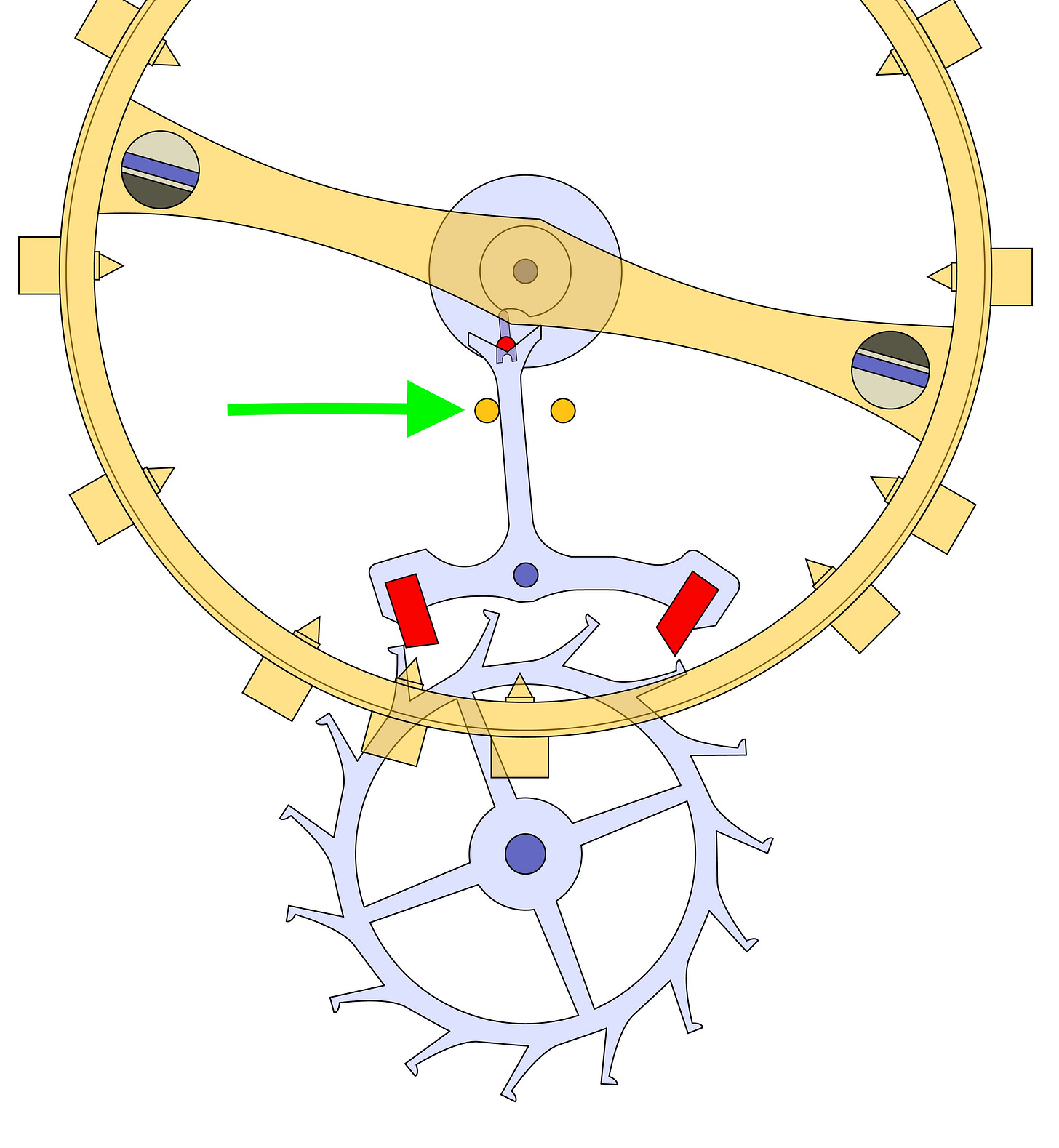

The second, is that there is “the magnetic equivalent of draw” (as described by the watchmaker) in the escapement. Although not shown in the diagrams from Breguet, there are banking pins on either side of the long shaft of the lever, which act to limit the arc of its movement; these perform the same function in a conventional lever escapement:

In this diagram (via Wikipedia) the green arrow points to one of the banking pins. The escape wheel (blue) is rotating clockwise, and pressing against the locking face of one of the ruby pallets (red). This produces “draw” – a mechanical pressure, holding the lever locked in place on the banking pin, until it is unlocked by the impulse ruby (red) passing through the fork of the lever.

Breguet’s watchmaker explained that “there is the magnetic equivalent of draw” in the magnetic escapement.

Each of the magnetic rings is divided into ramps of increasing thickness, with a large raised step at the end of each ramp:

The pallet dropping into the space between the escape wheel teeth passes over the thinnest segment of one of the ramps – there is a weak repulsive force, but it’s not as strong as that pushing the impulse pallet out of the escape wheels. Once the impulse pallet has cleared the large step at the thick end of its ramp, the escape wheel stack is free to rotate under the power of the gear train and mainspring. The pallet dropping into place encounters this step, whose magnetic field exerts a lateral repulsive force on the pallet:

… pressing the lever against its banking pin. (The lateral repulsive force is also what stops the escape wheel stack from rotating). The lever is now locked and will not move until the balance lifts it away from the locking position, via the impulse ruby. The repulsive force also locks the escape wheel in place, until the lever is unlocked by the impulse jewel on the balance.

Breguet’s watchmaker also explained that another reason a physical stop is desirable, is because repulsive magnetic fields don’t provide a clearly defined point at which movement stops. Instead, they act more like repulsive springs, producing an oscillation, like two ring magnets on a rod:

Cheers to the good folks at Apex Magnets.

This is something which hadn’t occurred to me at all. Having a physical stopping point is therefore an important feature in ensuring that locking takes place accurately, both physically and in terms of timing.

It is definitely true that the stop wheel is a safety feature – what is now clear, is that it is not only active if the watch is exposed to a physical shock. Rather, it’s an essential element in ensuring that locking, unlocking, and impulse take place. Writing for Watches by SJX, David Ichim conjectured:

“From the promotional materials, it is unclear whether the lever blocks the escape wheel exclusively through magnetic force, or locks softly against the safety wheel teeth. Even if slight contact occurs, the strength of the magnetic barriers should cushion the interaction and then separate the parts before the impulse is delivered [emphasis mine].”

As it turns out, brief contact followed by (very) slight separation is exactly what happens; this is indispensable to the reliable action of the escapement overall.

Another interesting feature of the tourbillon design is that the escape wheels are driven by an intermediate wheel – this allows the tourbillon to gear down to rotate once per minute; without it, it would rotate much quicker thanks to the 10Hz frequency of the escapement and could not be used as a seconds indicator.

The whole thing has been a bit of an object lesson in not putting too much weight on patents for clarification – I’m an habitual patent browser and always try to view the relevant patents if time allows but there are it seems to me, always good reasons to look out for changes made in the actual implementation of a design which may not be specified in a patent grant. Caveat lector.

Here’s my best shot at describing the action of the escapement:

The impulse pallet A has struck the face of the stop wheel and recoiled. It is now held in position by “magnetic draw” of the lever against one of the banking pins. The other pallet B has been lifted completely clear of the escape wheel stack and given impulse to the balance, and is now ready to drop.

The balance rotates, and the impulse jewel enters the pallet fork.

The impulse pallet A unlocks and is repelled away from the step at the top of the magnetic “ramp.” The repulsive force between the pallet A and the step, is still strong enough to hold the escape wheel in place, and prevent its rotating.

The repulsive force on impulse pallet A is transmitted by the lever to the impulse jewel, giving impulse to the balance.

As pallet A travels free of the escape wheel stack, the repulsive force diminishes until it’s low enough that the going train can now cause the escape wheel stack to rotate. Pallet B has already dropped into place.

As the escape wheel stack rotates, the stop wheel makes contact with pallet B and recoils very slightly, under magnetic repulsion between the steps on the ramps of the upper and lower escape wheels. Pallet B is now held in place by “magnetic draw.” The gear train via the escape wheel stack has provided the energy necessary to reset the magnetic potential energy of the escapement, and the escapement is ready for the next impulse cycle.

As I said in my coverage for The 1916 Company, I think a useful way of thinking about the escapement is as a transducer – that is, a device for transforming mechanical energy into magnetic energy, and back to mechanical energy again. Of course, answers also create more questions – for instance, is there any lubrication necessary at the stop wheel’s point of contact with the pallet (maybe to prevent impact corrosion?

The information I have so far makes me wonder how on earth it was made to work reliably. Every escapement requires extreme accuracy in manufacturing and adjustment, of course, but the Breguet magnetic escapement seems to necessitate a series of steps in its action whose precision may be measurable in fractions of microns. It seems like one of those mechanisms which either works really well or doesn’t work at all. If you are curious about technical watchmaking, it is definitely a gift that keeps on giving – just in time for the holidays.

Well worth a revisit now that you’ve heard directly from the horse’s mouth. I dream of a large scale model of this thing with proportional magnets so I can feel like I really understand it. Thanks to you and Mr. Flum for working so hard at explaining it to us!

Absolute clarity. Definitive accuracy. Fascinating to read. All at the same time. In one article. Hell, in every article. This is so rare these days that, well, I'll quote Lotus, from this same comment section: talk about "exotic animals"! Jack, you are one of a kind, in the best possible way. Don't ever stop doing this!