The Driver's Watch Is A Great Idea That Actually Never Was

At least, not the way we think.

It’s 1976. The 1973 Energy Crisis is still a fresh wound in the hearts of every red blooded American car lover, but that hasn’t stopped the auto industry from producing some of the most rip-snortin’ powerful muscle cars in its history. 1976 is the American Bicentennial, and in celebration, you’d think an American car enthusiast would opt for a Pontiac Firebird, or a Trans Am, or a Chevy Monte Carlo – anything with a big displacement engine, the aerodynamics of a grand piano, and enough torque to make air resistance irrelevant, at least from zero to 30 mph. But not you. No, you’re a suave, urban sophisticado and your hard earned car budget’s going for something a little more inside baseball and a lot more exotic: a wedge shaped piece of automotive modern art called the Lotus Esprit. Sure, it doesn’t have the massive raw power of a Detroit muscle car but just look at her – the sleek styling, the pleasant handling; a car so sexy that even though you don’t know it yet, it’s going to be the star car of the next James Bond film, 1977’s The Spy Who Shagged Loved Me, where it can convert itself from road car to submarine.

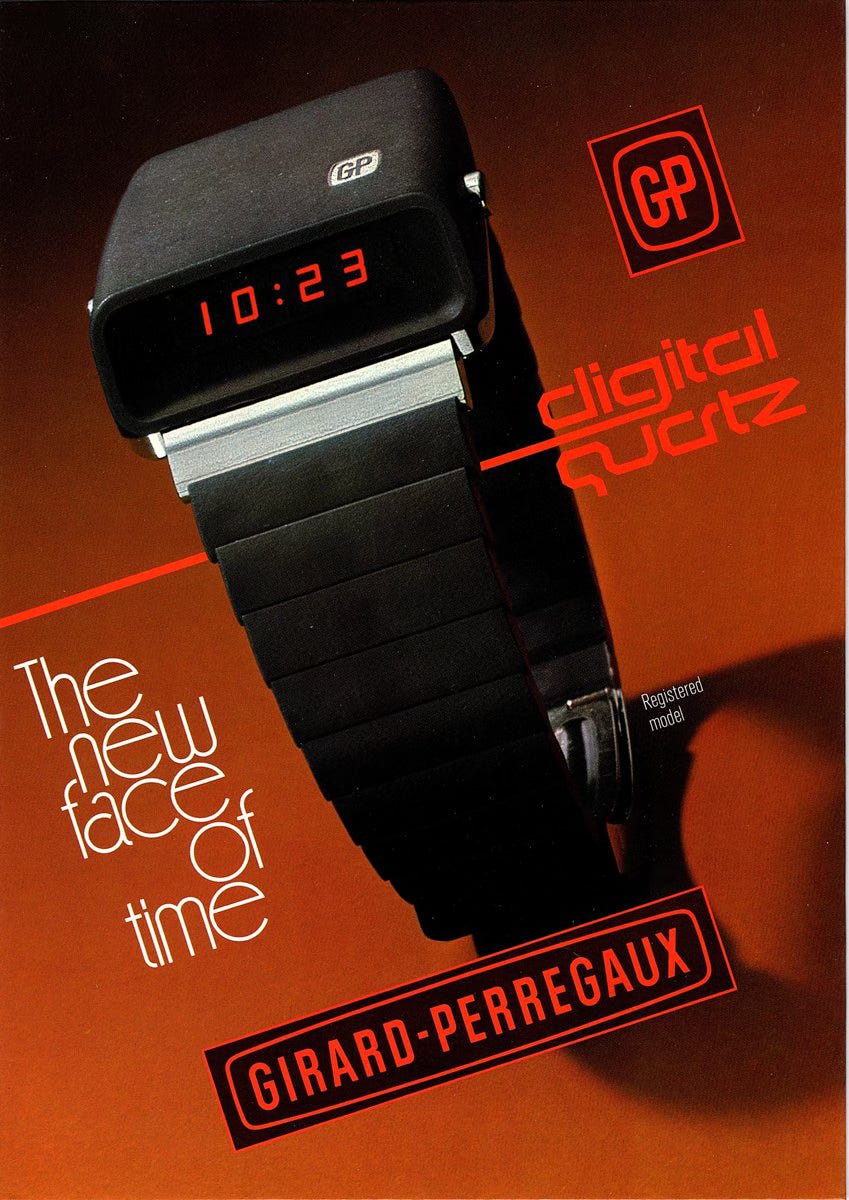

And to go with this euro-cool Italian-designed piece of auto-eroticism, you need a watch. And you know just what you’re going to get: the just-introduced Girard Perregaux Casquette, the latest in push button Light Emitting Diode technology, a watch for the discerning design lover – and, you think, the perfect driver’s watch, with its display set into the right-facing side of the watch (when worn on the left wrist) to make telling the time child’s play, as you guide your newest toy along the sensual curves of the Pacific Coast Highway, turning heads in every picturesque town through which you pass, and amazing the drivers and passengers of every car you overtake. Just north of and approaching San Francisco, with the whitecaps of the Pacific Ocean glistening off your right window, you decide to check the time on your wonderful new state of the art watch.

But what’s this? You can’t – the watch is LED, and will only show the time if you press the button. Forgetting all caution and restraint in your unslakable lust to mingle both a peak automotive and horological experience into a single singularity of electro-mechanical pleasure, you lift your hands off the steering wheel and press the button on your watch, bringing the display to blazing life. But curses! You’re holding the watch at slightly the wrong angle. Squinting to see the time, you don’t notice that your motorcar has missed a curve and when a slight bump alerts you that things have just gone sideways, it’s too late – you are airborne and following a perfect parabolic arc to a nose down landing in the ocean, and unfortunately for you, your Lotus isn’t a submarine. An instant before the almost surrealistically blue waters of the ocean part briefly and then close over your head, it occurs to you that you have indeed created the memory of a lifetime – it’s just going to be a very short one.

The term driver’s watch can be applied plausibly to an almost infinite number of different watches from various brands, makes, and models and includes any number of timepieces which have been created with the motorsports or automotive enthusiast in mind. The classic examples including the original Omega Speedmaster, which was marketed in 1957 as a wrist computer for drivers, and there are many other such examples too numerous to mention – usually, but not always, chronographs. For our purposes, however, we’re going to look at three different types of watches that are often claimed to have been specifically designed to make it easier for a driver to read the time without taking their hands off the steering wheel: side display watches, mostly but not exclusively LED; watches with crowns and 12:00 markers offset from the vertical axis of the watch (like the Vacheron Historiques American 1921) and finally, watches designed to be worn on the side of the wrist, like the Marvin Motorist, Gruen Ristside, and the Patek Philippe ref. 139. Let us now consider each case.

Lateral Display Watches: The GP Casquette, Bulova Computron, Amida Digitrend, And Others

The basic issue with the idea that these watches were ever intended as driver’s watches, is that there is one fundamental problem: they would have been perfectly terrible for telling the time when driving a car.

The first argument against them having been intended as driver’s watches, is illustrated in the opening anecdote; LED watches require you to push a button on the side of the case in order to illuminate the display. Why it has taken me so long to notice this fatal flaw (at least from a driver’s use-case perspective) is anyone’s guess – surely someone must have noticed it before me – but this problem alone seems to dispose, in one fell swoop, of the idea that such watches were ever aimed at drivers. In fact they are so unsuitable for use while driving that the idea is on par with suggesting that screen doors were specifically designed for use in submarines.

The other problem with any lateral display watch is that even in the case of mechanicals, like the Digitrend, they are difficult to read. The Digitrend is one of the coolest watches currently in production – I reviewed one for The 1916 Company not long ago and I thought it was pretty nifty – but the idea that a display you have to view through an angled prism at the bottom of a narrow field-of-view recess, is “easier to read” seems increasingly and obviously wrong the longer you think about it, and does not survive a single exposure to a side-display ana-digi watch.

Finally, there’s historical evidence. I’ve looked at a number of ads for the Casquette, the Computron, the Digitrend, and the Synchronar (an early and quite fascinating solar powered LED watch from 1972, built by Ragen Semiconductors) and there is absolutely no mention whatsoever in any advertisement or marketing material of using one as a driver’s watch. Absence of evidence, of course, is not evidence of absence but between poor legibility, no contemporary support for the idea, and the need for two free hands to operate them, I think the idea that these are “driver’s watches” is on very thin ice indeed. As the New York Times wrote, in 1975:

“Neither model could qualify as the ultimate digital watch for drivers. The L.E.D. takes a free hand to push the button to light up the time, and the L.C.D. sometimes takes a sharp eye to read it.”

Watches With Offset Crowns, Like The Vacheron Les Historiques American 1921 And Its Historical Antecedents

I am not sure where the idea that such watches were designed to make the time easier to read with your hands on the steering wheel came from – I can’t remember hearing about any such use case for such watches before the 2008 launch of the 1921, and a review on PuristSPro from 2010, which is laudably detailed and worth a look (I’d forgotten all about the perpetual calendar version of the 1921) makes no mention of the new watch or its vintage predecessors having been intended for driving. Vacheron Constantin’s Christian Selmoni has also gone on the record on several occasions saying that there’s no evidence in Vacheron’s archives, of any kind, for the “driver’s watch” story.

However, there’s another much more mundane and far more plausible explanation for the existence of offset crown watches. Stan Czubernet, the author of several books on vintage trench watches, including The Inconvenient Truth about the World's First Waterproof Watch, the Story of Charles Depollier and his Waterproof Trench Watches of the Great War, has done extensive research on such offset crown watches – many of which were made by American brands like Waltham, and which considerably predate 1921 – had this to say by DM:

“When the offset crown cases were made during the early years of WW1 they were NOT called ‘driver's watches’ … The reason these offset crown trench watches originally came to be is because of the American war effort. Your standard American made hunting case configuration movements were mostly being used up for military watches (size 3/0s and 0s). There was in fact a shortage. But, there was an abundance of American made open face configuration movements with the crown at the 12 o'clock position. So, the American case manufacturers like Philadelphia, Keystone, Bates & Bacon, Star and Illinois only had to make a slight change during their manufacturing process to produces offset crown cases that would nicely accommodate open face style movements. By doing so, this drastically increased the number of military style trench watches that would be available to our men going to France … The Americans started making offset crown trench watches in 1915. You can identify the earliest versions of these trench watch case made by the Philadelphia Watch Case Company by looking at the inside of the cases backs, none of them have serial numbers. They didn't start using serial numbers on these type of cases until 1916.”

While there are a number of scans of vintage trench watch advertisements online, advertisements showing offset crown trench watch/pocket watch adaptations are very rare. Czubernat says:

“Offset crown trench watch advertisements are quite rare considering how many of these watches were made in the WW1 years. Virtually every major American case manufacturer made this configuration by 1917. I've only found a small number of these adverts in my years of research.”

Here we are getting somewhat into the realm of speculation but it may be that the lack of advertisements reflects what was already a preference in the market for a crown at 3:00. An offset crown is charming to modern eyes, but it’s less practical than having the crown at 3:00, where it can be more easily manipulated (and a 3:00 is obviously more practical than a crown at 12:00 as well). In any case, offset crown wristwatches seem to have vanished from the market after the end of World War I, presumably because movements and dials intended for open faced pocket watches with 12:00 crowns, no longer needed to be adapted as wristwatches, as wristwatches proper began to dominate the market.

Perhaps one of the strongest arguments, other than historical evidence, for an offset crown watch not being specifically designed for drivers, is that no company with a history of making watches aimed at automotive and motorsports enthusiasts ever made one. Adrian Hailwood, founder of The Watch Scholar, looked into this question some years back and said via DM:

“Of course the clincher is that if it provided any benefit to motorists, Gallet and Heuer would have offset all their racing dials as would Omega for the Speedmaster and Rolex for the Daytona. They didn't because it doesn't. Interestingly Guigiaro designed an offset chronograph for Seiko's Spirit collection, but this was for motorcyclists where the wrist position is different.”

Wrist-Side Watches, Like The Gruen Ristside And Patek Ref. 139: Having seen that neither offset crown or side-display watches can plausibly be described as “driver’s watches” (with the caveat that if anyone can find even one couterexample for either or both – a contemporary advertisement, description, or other marketing material – we can now turn to watches designed to be worn on the side of the wrist. Here we are on much more solid ground. Not all advertisements for all such watches show a driver’s use case, but enough of them do that it seems obvious that, at least in some instances, that’s exactly the what their makers intended for them. The Gruen Ristside is one example and the Marvin Motorist is another, and in the latter case, “motorist” is in the name of the watch, which seems pretty unambiguous.

I have been unable to find anything confirming that the Patek ref. 139, which Phillips says was produced from 1933 to 1936, was marketed as a driver’s watch, however I would say on the strength of marketing materials from the same era for similarly configured watches, it’s a reasonable possibility.

There are some watches with similar configurations which were not specifically marketed for drivers; the Bulova Rite-Angle is one.

“The greatest improvement in the wrist watch since the advent of the wrist watch itself” seems a little hyperbolic, but it was a cool idea.

Generally, though, such watches seem to have gone the way of the dodo – it would take some digging to find out just when the last one was produced, and by whom, but they seem to have had their floruit in the 1930s, with the post-World War II “driver’s watches” being simply conventionally worn, larger, highly legible watches, which were often chronographs. Such watches don’t seem to actually offer any better experience when driving, than a conventionally configured watch with a large dial and high contrast markers and hands.

The Driver’s Watch: Never Let The Truth Get In The Way Of A Good Story: It doesn’t look good for the so-called driver’s watch, with the exception of a small number of wrist-side models made in the ‘30s – for the offset crown and side-display alleged models, a look at their impracticality, absence of any added utility, and lack of historical verification paint a pretty gloomy picture. I suspect, however, that offset crown and side-display watches will continue to be referred to as driver’s watches, probably for the foreseeable future, in the same way that “dynamic water resistance,” the unsuitability of 100M dive watches for diving, the Cartier Crash resulting from a high speed car accident, and other horological urban legends keep cropping up. The problem with the idea is that it sounds perfectly reasonable. However, who knows what could crop up. All it would take is one advertisement for an offset crown watch from the early 1900s showing it used as a driver’s watch, and I’d have to eat my snap brim fedora. But I’m not holding my breath.

Big thank you to Stan Czubernat, who may have looked at more offset crown trench watches than any other human alive; find his trench watch archives at LRFantiquewatches.com. Thank you also to Adrian Hailwood, who kindly reminded me by DM that he and I had discussed exactly this issue more than two years ago; Adrian is the founder of The Watch Scholar, and provides authentication, valuation, editorial, and other services.

To folks waiting for part 2 of the Seiko Black Monster review – coming up shortly!

Hi,

When pocket calculators came out in Oz,the screen was LED the battery life was lower than the basic wage.

So I guess that’s why they had an on /off switch.

Here we drive (RH)with the left arm and the other with the elbow out the window.

BTW what’s an airbag?

This is wonderfully groundbreaking work.